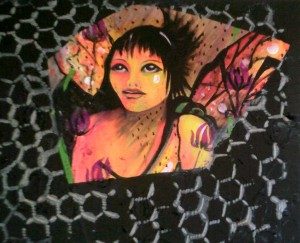

Fairy. Art by DuBrae 2012.

Bruno Bettleheim wrote:

“In order to master the psychological problems of growing up and overcoming narcissistic disappointments, productivity and oedipal dilemmas, sibling rivalries; becoming able to relinquish childhood dependencies; gaining a feeling of selfhood and of self-worth, and a sense of moral obligation –a child needs to understand what is going on within his (or her) conscious self so that he (or she) can also cope with that which goes on in his (or her) unconscious. He (or she) can achieve this understanding, and with it the ability to cope, not through rational comprehension of the nature and content of his (or her) unconscious, but by becoming familiar with it through spinning out daydreams – ruminating, rearranging, and fantasizing about suitable story elements in response to unconscious pressures. By doing this, the child fits unconscious content into conscious fantasies, which then enable him (or her) to deal with that content” (my parentheses). [1]

The psychoanalyst Marie Louise von Franz suggested that the fairy stories told to children in their formative years are more than exaggerated tales. The social and emotional fairy stories have a huge impact in the shaping of children’s developing minds. Franz suggested that children connect incidents to their favourite tales and the struggles they face in their every daily life.[2] As the theory goes, children who have heard fairy tales from a young age are introduced to some of the problems they fear the most, which include the death of a caregiver, violence or being taken away by a stranger; a wicked witch.[3]

The theorists have suggested the real fear for a child is that of abandonment and loss. In fairy tales these traumas are presented in such a way that the child is believed to feel safe and protected because the setting is more often a magical place in a make-believe land, (once upon a time,) a long time ago.

The psychoanalyst Bruno Bettelheim said that “no sane child ever believes that fairy tales describe the world realistically” but “every child believes in magic, and (s)he stops doing so when he or (s)he grows up”.[4] (My parenthesis.)

In the earliest moments in our childhood we endeavour to acquire some kind of unity between body, mind and those around us, just as we try to find a connection between ourselves and the magic in the stars and the universe. We imagine, but connection does not come automatically, we have to practice using our instincts and first learn how to connect with our immediate surroundings. As we grow the attention shifts from the ephemeral universe to the material world and we find a different connection in objects and people who have since become objectified. We live in a world of objects that cloud our subjective experience and this is one way of losing our primary identity and invoking the experience of primary trauma; but there are many more occasions where trauma enters our lives. Not knowing who we are or where we belong is a feeling of abandonment. For most, understanding life begins with some form of identity. Who am I? Where did I originate from? Why do I feel different or abandoned?

We form our identity in relation to other people, we learn their beliefs, copy their ideas and sentiments and act out their behaviours in much the same manner as history and polity has dictated. We acquire these doctrines of life through our families, friends, relatives, kindergarten, schools, the workplace and from our environments. We learn from real stories, fairy tales, religions, historiographies, images and texts as well as sublimation and all the other fictions surrounding us; and we create ourselves as a fiction.

[1] Bruno Bettleheim 1976. The Uses of Enchantment. UK Penguin, p117.

[2] Marie Louise von Franz 1996 The Interpretation of Fairy Tales Shambhalah Boston London.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Bettleheim Ibid.